Berlioz and Britain by Colin Bloxham

Credit: Oxford International Song Festival – Oxford International Song Festival | Oxford Lieder (oxfordsong.org)

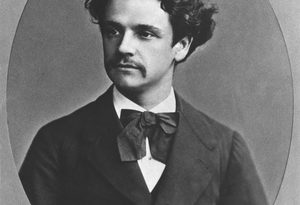

Hector Berlioz, one of the “greats” of the music world, was born in 1803 in the department of the Isère in the small town of La Côte-Saint-André, which now hosts the annual Berlioz Festival. His family wanted him to become a doctor, but despite completing his studies at the University of Grenoble and then in Paris, he was determined to embark upon a musical career from an early age. He was what might be described nowadays as a “free spirit” with passionate impulses. He fell in love very easily, it seems, not always happily. His feelings for a number of women were frequently not reciprocated. He was also passionate about literature and, along with Virgil (the source for the libretto of his opera Les Troyens), discovered that Shakespeare accorded well with his impulsive and colourful personality.

Berlioz’s knowledge of music was largely self-taught, but he did manage to gain admission in 1826 into the Paris Conservatoire following his medical studies and performances of early works such as the Messe solennelle andLes Francs-juges. His style was too idiosyncratic for the more conservative tastes of the Conservatoire. Nevertheless, he was able to modify it sufficiently to win the prestigious Prix de Rome. He did not value highly his time in Rome, despite meeting influential figures such as Felix Mendelssohn. The start was marred by the abrupt termination of his engagement with Marie Moke.

Shortly after his return to Paris, Berlioz enjoyed success, especially in December 1832, when a concert at the Conservatoire attracted musical luminaries such as Liszt, Frédéric Chopin and Niccolò Paganini as well as literary figures: Alexandre Dumas, Théophile Gautier, Heinrich Heine, Victor Hugo and George Sand. Also present was an English actress, Harriet Smithson. It marked the beginning of another passionate relationship that culminated in 1833 in marriage at the British Embassy.

Throughout the 1830s Berlioz’s career alternated between failure to establish himself in the all-important world of opera and success with his symphonic concerts. In 1839, he revived Harold en Italie. The celebrated violin virtuoso Paganini was so impressed that he gave a very substantial cheque to Berlioz. This enabled him to focus on composition and the subsequent presentation later that year of several performances of the “dramatic symphony” Roméo et Juliette for voices, chorus and orchestra. The young Richard Wagner was profoundly influenced by the work.

Sadly, Berlioz was unable to sustain this success in France during the 1840s. Instead, he sought his fortune further afield: Belgium, Germany, Austria, Hungary and, notably, Russia, where his impact on the younger generation of composers – including eventually Tchaikovsky – was significant. In 1847 Berlioz made the first of five visits to London, initially as a conductor at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, with performances of his own works following in 1848. He was warmly received by the musical world, by critics and by wider society. A performance of his Symphonie funèbre et triomphale was given at Buckingham Palace in the presence of Prince Albert. However, the stay was overshadowed by the bankruptcy of the promoter of the Theatre Royal season. Meanwhile, in France, the political upheavals and revolution of 1848 made it increasingly difficult to find success at home.

Further visits to London were more successful. According to Gramophone magazine, “he was hugely admired…his conducting was much praised, his use of orchestral colour evoked comparison with JMW Turner’s paintings”. The concerts were popular apart from Benvenuto Cellini, a failure at Covent Garden (opera house) in 1853. Berlioz continued to be well received too in Germany, where he was respected for the advances made in enhancing the potential of the orchestra and the development of musical form.

His was “the music of the future”, but not in France, where the indifferent reaction to his monumental opera Les Troyens was devastating. It was presented in an abridged form in Paris and did not receive a full performance until 1890 in Karlsruhe. The work languished, half-forgotten or only partially performed, until 1935, when a complete performance was given in Glasgow, albeit over two nights. However, it had to wait until 1947 before further signs of life became apparent, when Sir Thomas Beecham conducted a full BBC radio performance. Five years later in 1952, the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra made a recording of the shorter Les Troyens à Carthage. Then, in 1957, came the breakthrough production of the slightly trimmed full work at Covent Garden under the baton of Rafael Kubelík, which played a key role in reintroducing Berlioz for the modern era.

Among the people who experienced the production was David Cairns, who went on to publish his translation of Berlioz’s Mémoires in 1969. This was followed by the most authoritative to date two-volume biography of the composer in 1989 and 1999. Not only was Cairns a fine scholar and writer, he was also a practising musician. He founded the influential Chelsea Opera Group during his time at Oxford, where he later became a Visiting Fellow of Merton College. The young Colin Davis was also a member prior to him becoming one of the world’s leading conductors and a very important champion of Berlioz.

The young Sir John Eliot Gardiner was also won over to Berlioz at this time. He went on to conduct the first complete performance of Les Troyens with his Orchestre Révolutionnnaire et Romantique at the Théâtre du Châtelet, 200 years after the composer’s birth. This was just one of the many occasions on which Gardiner brought to the attention of a large public the breadth of Berlioz’s work through inspired concerts across Europe and beyond. The ORR has pioneered concerts that replicate the sound and instrumentation of the period in which the music was composed, notably performances and a celebrated recording of the mighty Symphonie fantastique given at the Paris Conservatoire, where Berlioz himself introduced the work to the world.

Other British musicians have also been devoted champions of Berlioz: Sir Colin Davis, Sir Simon Rattle, Roger Norrington, Sir Thomas Beecham and John Nelson, whose recording of Les Troyens won the 2018 Gramophone magazine Recording of the Year award. Gardiner remains probably the most significant.

In 2013, Berlioz’s biographer, David Cairns, was appointed Commandeur dans l’ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Bernard Emié, French Ambassador to London, commented, “It’s fair to say that the modern Berlioz revival largely began in the UK. His finest successes, today in Parisian concert halls are due largely to the passion of British conductors.”

Vive l’amitié anglo-berliozienne!

Notes:

- With thanks to Gramophone magazine.

- Further reading: Hector Berlioz: music’s great revolutionary | Gramophone;

- The Hector Berlioz Website – Champions: David Cairns (hberlioz.com);

- Berlioz: Les Troyens CD review – electrifying performances set a new benchmark | Classical music |

- The Guardian The Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique celebrates its 30th anniversary | Monteverdi Choir and Orchestra ;

- The Hector Berlioz Website – Berlioz in London (hberlioz.com)

- Sadly, the 2023 Berlioz Festival was marred by Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s assault upon a singer leading to his withdrawal from the Festival and from the Proms concert scheduled for 3rd September, at which he was due to conduct Les Troyens. Highly regrettable though the incident was, it is to be hoped that Sir John will resume his musical activities following a period of reflection and apologies.

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I am very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i am looking forward to contact you. Will you please drop me a mail?